by Jen Stevenson

The past 3 months have seen crazy, unprecedented weather. Hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria devastated parts of Texas, Florida and the Caribbean. Other massive storms in recent years, Joaquin, Sandy, and Katrina, show that bigger, badder weather is our new reality. As I write this, there is an actual flash flood warning and wind advisory in effect for a large chunk of New England; over 300,000 people are without power in Massachusetts, over 65,000 in New Hampshire, and over 350,000 in Maine. Coastal communities are particularly vulnerable to the wind and water damage that this climate change-caused weather can wreak.

Power outages can be the worst byproducts of storms. Outages can be just a minor inconvenience for some of us. But for the elderly, those with medical conditions, and facilities that both provide critical services and depend on employees being able to make it into work (like a hospital), a prolonged outage can be catastrophic. Factor in extreme heat or cold, and the situation is only amplified.

Keeping the power on boils down to grid reliability. So if one power plant or its transmission or distribution lines are incapacitated, all connected customers are at risk unless they happen to own a generator, which requires that they have fuel to operate it handy. In a big storm, like we are seeing with Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico, over 2.5 million people are still without power a month after the event. People are at the mercy of the utility being able to rebuild and restore power, and some predictions anticipate it will take six months to a year to get everyone back online. Can you imagine not having electricity between now and Christmas? Between now and next Labor Day?! That means: no stove, refrigerator, microwave, washing machine, lights at night, hot water, tv, Netflix, and gasp no way to charge your smartphone! FOR. A. YEAR.

What if there was the option for a more localized source of electricity that wasn’t dependent on the utility’s large-scale power grid? An option that, even if it did get knocked out of commission, could be back up and running in less time since there is less infrastructure to repair? This option exists! It’s called a microgrid. My favorite analogy for a microgrid is that it’s like a community-sized generator that runs on a combination of solar power and batteries. There are different types of microgrids. Some are connected to the electric grid, some are not. Some use renewable energy like solar panels and others use propane and diesel generators. Many use a combination. Regardless, their strength comes from the fact that they don’t rely on a larger system and that independence increases their reliability factor. In other words, even if your electricity provider is down, you can still draw power from your microgrid. And it seems like an ideal option for places like Puerto Rico.

One of the reasons microgrids haven’t taken root yet lie in the weaknesses of renewable energy. (Yes, renewables have weaknesses.) Solar produces the most energy when it isn’t needed. For example, people don’t need to turn on the lights when it’s sunny, but that is when solar panels (PV) are in max production mode. Being able to save that energy for it to be deployed at a later time would cancel out that flaw. Major advances in energy storage, aka batteries, have been made in the past few years. Adding battery storage to the PV equation could make solar energy usable when the sun isn’t out. Together, PV and battery storage create efficient, green, reliable electricity that stands a better chance of weathering a storm, literally.

Batteries as they relate to energy storage can come in many shapes and sizes. The number of batteries used depends on the size of the microgrid. The shipping container on the left holds many large batteries; a microgrid could employ several containers worth of storage. On the right is an example of Tesla’s Powerwall, which makes batteries scalable; you can connect as many Powerwalls together as you want. Like Legos!

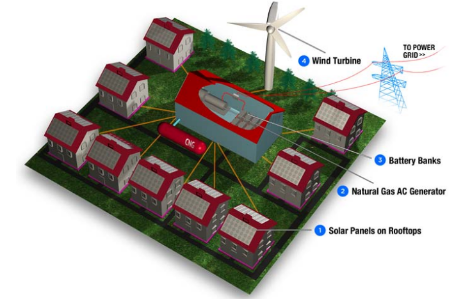

What does a microgrid look like? Well, it’s decentralized, but the recipients of the energy it produces are in close proximity. Solar panels can be placed in the areas best suited for solar power (not shaded by trees or other buildings); they don’t all have to be in one place. Batteries housed in shipping containers can be placed elsewhere, like on an empty lot or near an existing substation if the microgrid will be connected to the grid. It may not look like there is anything really there, but the recipients know otherwise.

This graphic from Cleanskies.org demonstrates how a microgrid is decentralized.

The benefits of a microgrid go beyond just providing power in an emergency. They have plenty of applications. They can provide power all the time or they can supplement the electricity a community buys from the grid, ideally during “peak” hours, which is when electricity costs the most money. They can sell electricity back to the grid. They can power charging stations for electric vehicles or cell phones. They can create jobs since local people are needed to install and operate them. They cut down on greenhouse gas emissions if they use renewable energy sources. Depending on their organization and size, they can be a real asset to any community, but especially those that frequently experience blackouts.

We are excited about how microgrids have the potential to help solve some of Puerto Rico’s problems, and we are partnering with some other organizations to see if we might be able to make one a reality. The project is in its infancy, but if you would like to learn more or want to get involved, or if you are Elon Musk and you want to fund one, please let us know! You can reach us at info@climable.org.