by Hannah Mohtadi

How much money could we save in the future by investing in sustainability and green energy today? That is the question that climate advocates, economists and scientists have been asking for decades. We know that fossil-fuel related activities cause a host of negative externalities, such as public health costs related to air or noise pollution. These negative externalities occur when the cost from the production or consumption of a product is displaced onto a third party. Rather than holding the large corporations accountable for the lion’s share of emissions, these costs often fall on society. If we could prevent those future societal costs by making the shift towards renewables and resilient infrastructure today, the global economy could save billions of dollars. We call this idea the social cost of carbon (SCC).

The SCC is an estimate of the monetized damages associated with the increase in carbon emissions. It is established through a discount rate (or a dollar value for predicted future damages) per metric ton of carbon but requires A LOT of assumptions to be quantified. Economists must assume the socioeconomic trajectory and world changes of the next century, monetizing the damages related to agriculture, public health, property due to increased flooding, and changes in ecosystem services as a result of climate change. Essentially, economists are attempting to predict how the economy will change in response to extreme weather or disasters and with the uncertainty of climate change impacts, these calculations can be difficult.

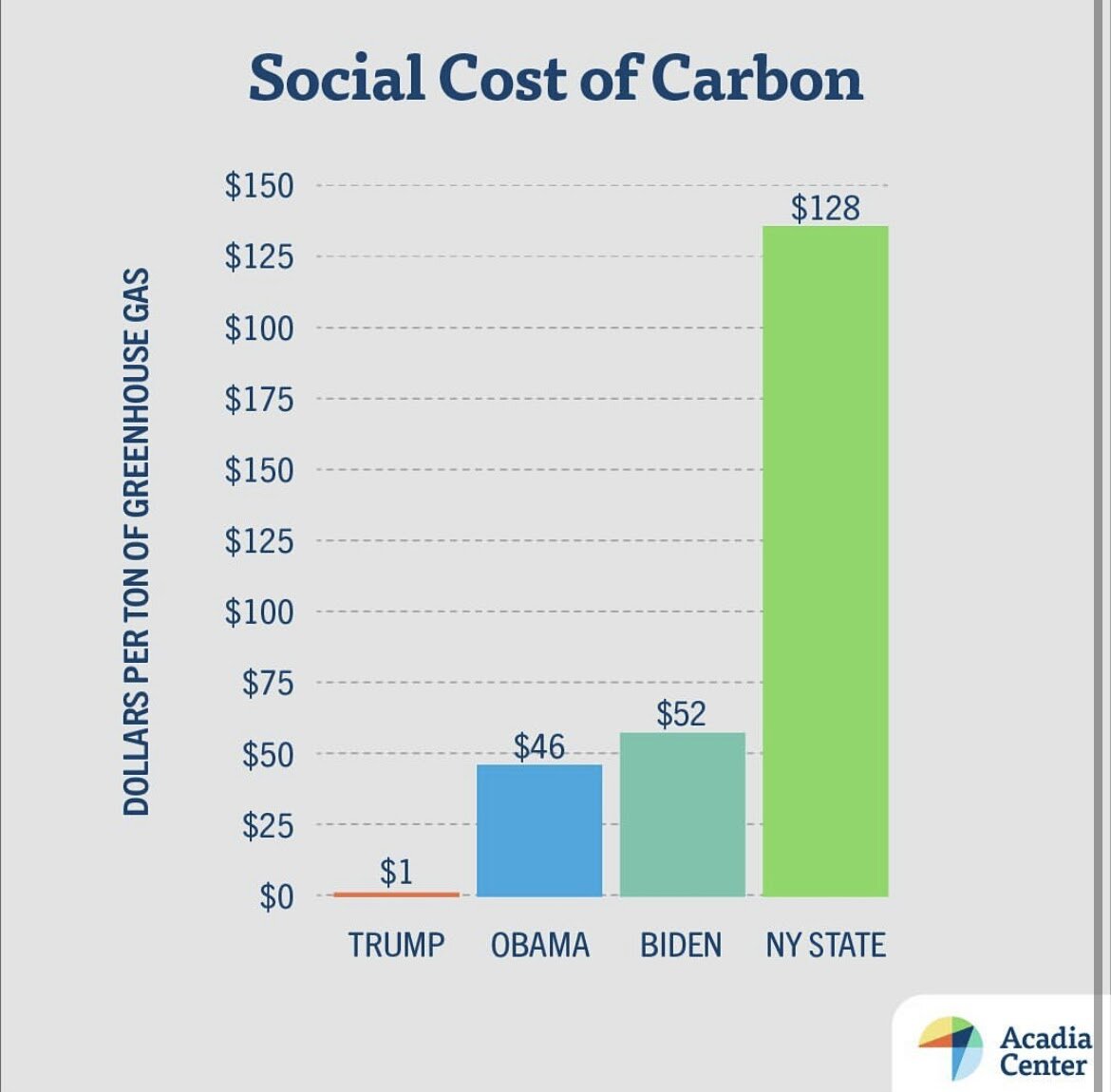

The Biden Administration recently released their guidance for the social cost of carbon: $52/ton. This is a pretty good improvement compared to past administrations, but we can do better. Image: Acadia Center

The discount rate in the United States has changed dramatically with each administration, since the Obama administration created the Interagency Working Group on the Social Cost of Carbon in 2009. The rate represents the predicted damages that will result if the US does not transition to renewable energy rapidly. By decreasing profits by a discount rate (often 2%, 3%, or 5%), officials attempt to make dirty fuels more costly to produce. The SCC serves as a policy tool, allowing agencies and policymakers to quantify the social benefits of reducing carbon emissions. This rate forms the foundation of many US climate policies, such as the Clean Power Plan. Government regulatory agencies employ the SCC discount rate to calculate the benefits of reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The rate serves an important role in long standing executive orders which often obligate federal agencies to consider a cost-benefit analysis for federal action that may have small, or “marginal,” impacts on cumulative global emissions. In addition, agencies generally employ the results of these analyses to justify a chosen course of action and rule out alternative pathways.

This graph demonstrates how a smaller discount rate actually means a higher cost per ton of carbon released. A discount rate of 2.5% has the highest impact at $123 per ton of carbon. Image: EPA

So, how does a discount rate work? A higher discount rate means that companies pay a lower cost per ton of carbon released. Politicians and economists justify this higher rate with the assumption that people will continue to grow wealthier and wealthier, and thus be better equipped to handle damage costs later on down the road. Additionally, they argue that there is a high opportunity cost involved, namely that every dollar invested in damage prevention today is a forgone investment in other places that might have higher societal returns in the future.

Advocates of lower discount rates, meaning a higher cost per ton of carbon, argue that climate change might hurt or altogether halt economic growth. They posit that overall incomes might rise but inequalities will probably increase as well. The communities, or even countries, most vulnerable to climate change damages might not experience that same rate of growth or have the future resources to adequately tackle the resulting costs. Another factor we can’t ignore is the external negative impacts that affect the entire world such as public health costs related to pollution or climate-related diseases.

From these two arguments, we see that calculating the social cost of carbon is not only a numbers game. Rather, it is a deeply ethical and philosophical process. As Frank Partnoy, Professor of Law and Finance at the University of San Diego, says about the social cost of carbon, “Ultimately, we can’t rely on only numbers — we have to make really hard value judgments. We should stop pretending this is a science and admit it is an art and talk about this in terms of ethics and fairness, not what we can observe in the markets.”

As we think more about what different discount rates say about our values, and how externalities should or shouldn’t factor into the true cost of carbon, we want to hear what you think. Stay tuned as we dig a little deeper in our next blog post, diving into discount rates, the carbon tax and so much more!