By Elana Manasse-Piha

Did you know termites are amazing architects? Their mounds have an amazing design that provides passive, natural cooling.

Termite mounds are a wonder of nature, providing insulation, temperature control, and gas exchange all through non-mechanical means! What we’ve learned from them is game-changing for keeping buildings cool without traditional and energy-intensive air conditioning.

From the outside, termite mounds look like a solid triangle of dirt emerging from the earth. However, the structure of a termite mound is intricate and impressive, especially when contrasting the size of the architects with their creations. The mounds can reach 30 feet in height and are built by animals with brains no larger than a grain of sand!

Fungus-growing termites maintaining a ventilation tunnel.

An example of a termite mound.

Termites don’t technically live in the mounds, but beneath them in underground nests. Living below a pillar of dirt sounds suffocating but one of the primary purposes of the mound is to keep fresh air circulating underground. In addition to having good airflow, mounds expel the CO2 produced by the termites and keep the temperature in the nest constant despite outside conditions!

Fungus-growing termites construct their mounds with a central chimney connected to small tunnels that end on the sides of the mound. As the sun moves, the mound and interior tunnels heat up faster than the insulated central chimney creating a temperature differential. The hot air from the tunnels plus the warm air in the nest rises and exits the mound. Meanwhile, the insulated cooler air in the central chimney sinks into the nest (thank you, thermodynamics!). The air current created by the CO2-saturated, warmer air rising out of the mound and the cooler air sinking into the nest, draws fresh air into the mound. This circular airflow, caused by the rising of less dense hot air and the sinking of denser cold air, is called a convection cell. At night, the process reverses, with the exterior tunnels cooling more quickly than the central chimney, flipping the direction of airflow.

Termite mound convection cell: Fungus-growing – open chimney (daytime).

Direction of convection cell flow in a simplified diagram of a fungus-growing termite mound throughout the day. As the orientation of the sun changes about the termite mound, the direction of the convection cell changes and splits into two convection cells at midday and night.

Using nature as an inspiration for innovations is called biomimicry, a prime example of which is termite mounds inspiring more efficient ways to regulate the temperature inside buildings. The architect Mick Pierce was inspired by termite mounds and other natural processes when he designed the Eastgate Center in Harare, Zimbabwe. He used the convection cell of the fungus-growing termite mound as a model to design a building that would not rely on conventional air conditioning.

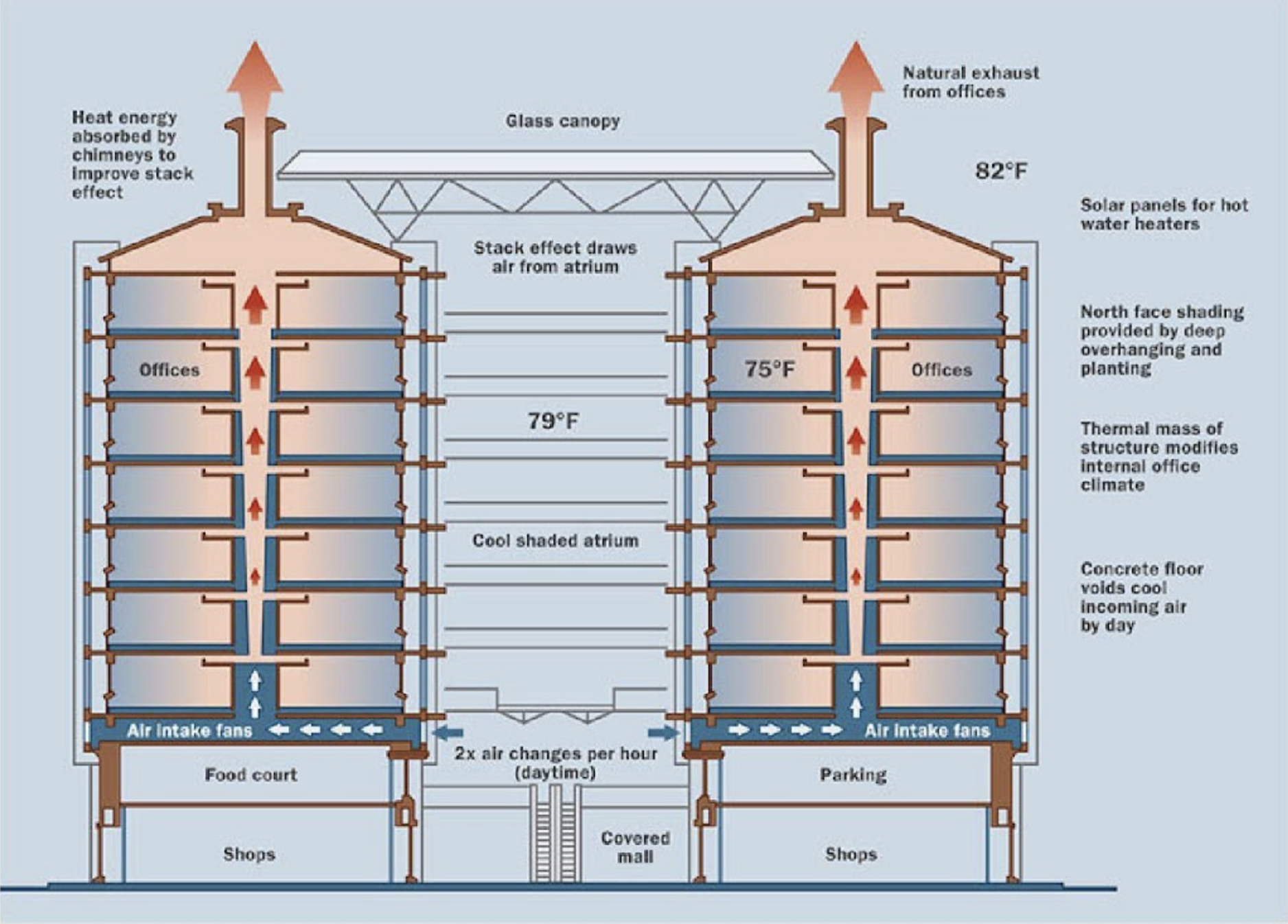

The structure of the Eastgate Center, completed in 1996, incorporates two buildings connected by a covered, open-air atrium. At the base of each tower are fans that push cool air, drawn in from the atrium, through ducts that lead through hollow floors. The fresh air is released into rooms from low-level grilles under the windows. As the air in a room warms due to human activity, it rises and gets sucked into exhaust ports in the ceiling. These exhaust ports lead to the central chimney, where hot air from all over the building is collected and allowed to rise and escape. The Eastgate Center was an undisputed success, consuming less than 50% of the energy than similar structures that rely on conventional air conditioning!

Schematic and airflow and temperature diagram of the Eastgate Center.

Airflow through an office in the Eastgate Center. Cool air from the atrium travels through the floors into the office. Once the air gets hot from normal human activity, it rises and exits through vents in the ceiling and travels to the central chimney where it is expelled.

Air conditioning is a growing necessity, but also a significant contributor to global warming. This juxtaposition of need versus harm necessitates a fundamental shift. Using termite mounds as inspiration to create self-cooling buildings is the type of innovation we need to solve such a complicated problem.

The Eastgate Center building shows what humans can do when we use nature as inspiration. Biomimicry has already inspired astounding inventions and is providing solutions to some of the thorniest problems. Biomimicry demonstrates what we can achieve when we look to nature for inspiration.